Notes to the English version (translated from http://karol3.blog.pravda.sk/2011/03/09/1/

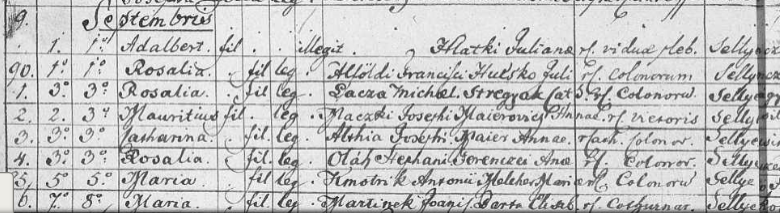

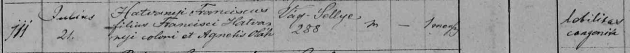

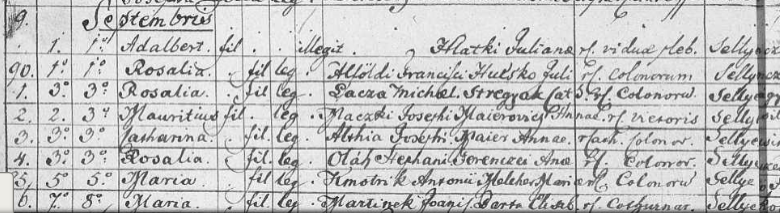

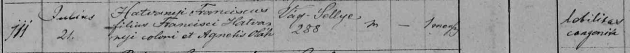

Karol Hatvani (but also Hatvany, even Hatvanyi), father of my father František, was born and baptised in Šal'a nad Váhom as Carolus Hatvani 15. 10. 1879 (https://familysearch.org/pal:/MM9.3.1/TH-1-14327-56989-37?cc=1554443).

His father was Franciscus Hatvani (profession inquil = sub-tenant, maybe casual worker), mother Rosalia Oláhová (1855-1931), a Gipsy girl (I was able to trace her ancestors as far as 1780).

His father died about two months before Karol was born (this information seems to be incorrect, refer separate entry under Karol Hatvani):

His father died about two months before Karol was born (this information seems to be incorrect, refer separate entry under Karol Hatvani):

Grandfather's wife Júlia, nee Maczki was born in Tardoskedd (Tvrdošovce), to where her parents, with some seven of her siblings, came from Heves in today's Hungary (2001). In Heves, according to the family tradition, they lost some properties to gambling. Great-grandfather's wife Rozália (known in the family as Rozanenna) after her husband's too-early death married a man called Viczena, and thus the grandfather had a few stepsisters and at least one stepbrother; this stepbrother lived in Kotešová near Žilina. His granddaughter and her daughter Zlatica (used to work at a pharmacy in Žilina) used to call on us in Bratislava for many years.

Grandfather served some four years in the Austrian army in Korneuburg (Eisenbahn und Telegraphen-Regiment). On the picture below he is in the middle, marked with the orange circle on his chest. He is also here in the corner aged about 75:

More about him can be found in http://hatvani-havelka.blogspot.com.au/2007/10/karol-hatvani.html

After 1900 he returned to Šal'a nad Váhom, found and married his girl Júlia (nee Maczki), and in about 1908 they started family at the railway house opposite the railway station Pozsony-Dynamitgyár, renamed after 1920 Bratislava-Dynamitová továrna. This is their family in 1917:

More about him can be found in http://hatvani-havelka.blogspot.com.au/2007/10/karol-hatvani.html

After 1900 he returned to Šal'a nad Váhom, found and married his girl Júlia (nee Maczki), and in about 1908 they started family at the railway house opposite the railway station Pozsony-Dynamitgyár, renamed after 1920 Bratislava-Dynamitová továrna. This is their family in 1917:

Four children were born to them in

that house, my father being No. 3; in that house they lived until the grandfather’s

retirement in 1940. The children were talented and made it fairly high in life:

the oldest son Štefan, became a steam-engine driver, which profession in those

days was as glamorous as an airline captain today (1999); older daughter Helen

worked for many years as managing director’s secretary in the nearby Dynamit

Nobel factory; younger son František (he preferred being called Karol) started

as a taxation clerk and retired as an editor in trade union publishing house;

younger daughter Rozália (Ruženka) worked all her life as an insurance

assessor. I was living with them since I was 6 (1942), until 1962, when the house was demolished to make way for tramway; my parents,

who, until 1949 lived in Nová doba 3 (on the edge of the Kuchajda plain) I saw

only seldom. Even after they moved to live with us in 1949 I preferred the

company of my grandparents and the aunts Ruženka & Helenka. The years 1942

up to 1949 were the happiest of my childhood. This is us all at around 1950:

|

Below we are sometime in 1953-54 on the occasion of the “old” couple of Lepiš and his wife paying us a visit (Helena was married to their son Fero). The picture was taken by my mother: |

The

fishpond was about 20 to 40 metres wide and as long as the strip of grandfather’s

land, some 400 metres. It was full of fish: pike, tench, perch, bleak, noisy loach, and

certainly other. On the bottom there were freshwater oysters, the frogs were

leaping into the water from the edge at every step. On its edge there lived non-venomous

grass snakes, among the reeds lived reedbirds and wild ducks, at night one

could hear strange voice of bittern, and when wind was blowing from the right

direction one could hear melodious voice of a woodpecker, even of a cuckoo,

coming from the forest on the nearby mountain (Chlmec). Beyond the railway

embankment, in the direction of Rendez, we saw several times a be-whiskered

bird I called ostrich. Many years later I discovered it was bustard. In the

same area there were larks, dancing hares, we used to be swooped by lapwings,

spooked by flocks of partridge noisily taking to wing almost from underneath

our feet, flocks of quail, and other birds and animals. Once, during a walk

with auntie Helen to the nearby vineyards we frightened a deer with huge

antlers, which started leaping in the deep snow towards the forest – that was

the only time I saw a deer in the Male Karpaty mountains. Occasionally I saw

men trying to catch water rats in Halatka fishpond, but I have never seen them

catching any. Once, with the grandfather, we needed to chase a bird called krivonoska away

from our sunflowers. We tried to shoot a pebble by using a slingshot, in her

direction, but, unfortunately, grandfather was “lucky” in hitting and killing

her. After the initial euphoria we were both sad for a long time. Some 50 years

later, on the same spot, I had a strange experience...

Halatka.

I came to see the place around Christmas, 2005. I saw it

from a train a few days before and struggled to find it: the railway lines

were relocated, and the entire area had been divided into a warren of small

gardens, with a house here and there of a kind any architect would turn his

face away from with disgust. I walked to the place early in the morning. The

visibility, due to the thick fog, was less than 10 metres, and there was a

fresh cover of snow up to my ankles deep. I was walking by memory along the Kasino

building, under the old railway bridge, the only recognisable points in my

memory. Behind the bridge I chanced upon a gap between the little gardens and

felt my way forward among heaps of rubbish and shrubs, all covered by snow.

All of a sudden, I felt a strong bellyache of a “lightning” type. So sudden and urgent it was that I was unable to resist – one more minute and everything is in the trousers! Next to a pile of broken concrete blocks I tore my clothes off, crouched down and relieved myself to an immense satisfaction. I was squatting there for some 10-15 minutes, washed myself down with snow, and with frozen hands slowly put several layers of clothing back on. I stood up and looked around: the fog dispersed somewhat, and visibility was perhaps 100-150 metres; I was able to see roofs of some houses along Račianska street. I recognised the roof of the Ceglei’s house, Valentin’s house, even the spot where my wife’s parents house used to stand. This is impossible, I thought!!! The spot I relieved myself was exactly the same spot where the grandfather killed the krivonoska (a songbird similar in shape and size to Australian lorikeet, or rosella)! It was exactly the same spot the entire family used for relief, among the stalks of corn or sunflowers, all those long decades ago!

A local inhabitant, 2004.

About

a month earlier I was on the edge of this little garden area with our older

son George. It was late autumn, but the leaves have not yet fallen completely from the

trees. The son was due to leave for his home in the overseas, and we were in the area

to take pictures of the remnants of the house where his mother spent her

childhood. The remnants we found in a rather poor state of repair – someone

used them to put together a primitive type of shed; we made a few photos, I

told him how it used to look, and we began to leave.

We hardly made ten steps,

when “Aaaaah, and what are you looking for here!?”, an angry sounding voice

rang from behind us. The voice belonged to somebody in the next garden; its

owner remained hidden behind a screen of shrubs. “Why do you ask?”, I said in

reply. “If you have no business to be here PISS OFF!”, the voice said, with a harsh

sound of the local accent. From that accent I guessed the owner to be an old

railway worker. I replied in kind with a few choice words, and we continued

walking. The stream of invectives from behind us included references to us

licking his posterior, to our dirtiness, to our cattle-like bad manners...

After about fifty metres my son remarked that the tone of the voice is a bit less venomous – what about returning and trying to get some information from him? The son’s understanding of Slovakian is quite good, but with no knowledge of any swearwords, or words spoken in the local dialect. We returned and sat down in the grass in front of the entrance to the voice’s garden. “And what is this?”, said the voice. Only now we were able to see its owner, albeit partly. He was still behind his shrubs, but I was able to make a kind of judgment: about 65-70 years of age (like myself), perhaps a railway worker, slim. “We would like to ask about something”, I said. It was something unexpected for him and so he continued with abusing us; my son tried to calm him down in a soothing voice, too.

Eventually he calmed down somehow, and “what is it that you

want?” he asked. “My wife spent most of her childhood here, your garden here sits in part of

her old property, and we would like to hear if you know anything about her

family.”

“Naaaah,

and what was her name?”

“Pipaš”, I said. It seemed to have rattled him a little.

“Naaaah,

and what was her father’s name?”

“Pipaš”,

I said again. The irony ignored, he continued “Naaaah, and what was his Christian

name?”

“Rudolf”.

“Eeeexactly,

Rudy”.

Finally he seemed a bit calmer. Us two likewise, for it suddenly seemed that he

might know something.

“Naaaah,

and what is your business in all this?”, he asked.

I

explained that Mr. Pipaš’ older daughter is my wife, mother of our son who sits

here next to me, “as I told you before you started abusing us”, I added, but

should have controlled myself better! He started abusing us again, kissmyarses

and similar ornaments were making the air around us thick. When his (rather

poor) vocabulary was exhausted I continued calmly that my wife is abroad, far

afar, and she asked us two to make a couple of pictures of her childhood place,

“as I told you before you started abusing us”, I repeated, unable to restrain

myself. To our surprise he answered equally calmly that “Rudy had two

daughters, both of them with rather dark complexion...”

“One

of them is my wife”, I interjected.

Unperturbed, he launched into a monotonous sing-song monologue, in a tad higher pitch than

until now:

“Yeeees,

Rudy had two daughters, both of them with rather dark complexion. People say

that both of them went abroad, nobody knows where.”

“One

of them is my wife”, I tried again, in vain.

“The

whole family disappeared, nobody knows where, maybe to Paris...”

“And

what happened to Mr. Pipaš”, I asked.

“Naaaah,

don’t you know it?”, he asked, with a hint of suspicion.

“I

know only that he was killed by a car at Rendez (some 3-4km distant)”.

“Yeees,

by a car.”

“I

heard he was drunk at the time”, I suggested.

“Yeeees,

the railwaymen are known for drinking”.

“And

was he really drunk?”

It

did not work this time. He became excited again, accused us of being spies who

can kiss-his-arse-as-many-time-as-they-like, and similar best wishes, until my son suggested that perhaps we have learned everything we could. We rose, said goodbye, and walked away. The loud abusing continued until it was drowned in the noise

of nearby busy road. Next day I bought a bottle of local gin called Anička,

wrapped it in paper and put it behind the front gate of his garden. On the

paper I wrote “from those spies to the old ass, and if you can’t read it ask

somebody who can” – I too, know how to be an old ass, if I put my mind to

it...

My wife.

My

wife’s parents Rudolf Pipaš and Mária neé Cingel'ová met and married in Belgium,

where they both worked in the district of Borinage. My wife was born in

Péronnes-Lez-Binche in 1940; her sister was born two years later in Buchloe in Germany,

where their father worked at the local railway station. The whole family made

it to Slovakia in 1945 to Radošina district, Rudolf’s home (Mária’a place of

birth was nearby Terchová). They lived for a while in the castle at Obsolovce.

In 1946 Rudolf found a job with railways in Bratislava, where he was given accommodation

at the Railway house No. 1 on Račišdorfská ulica; the house had a piece of

agricultural land attached to it (including a portion of it in my grandfather's old strip of land). That is where I met my future wife, she

6-years old, me 10. Our families knew each other but were not especially

friendly – the Pipašes were by the neighbourhood regarded as solitary people.

My wife’s sister Margita was bit of a friend with my sister Hanka.

Local boys.

In

wintertime Halatka froze over and became the stage for many a furious

ice-hockey match. The ice used to be rather thin, especially at the beginning

and end of the winter, and it was undulating up and down depending on the

movement of the players. We were used to it and we broke it but on a rare occasion.

The adults, or children who used to come only occasionally, used to regularly break

it and take a good dip in the icy-cold water. The water was seldom deeper than

to our neck, and the whole affair always ended with loud peals of laughter

(from our side, of course). The Czechoslovak ice-hockey national team at the

time was best in the world, and we used to play under the names of its players

– Zábrodský was the most popular name, Bubník, Konopásek, Roziňák; I use to

play as Troják, but once, as a goalkeeper by the name of Modrý, I sustained smashed

lips and a few loose front teeth from a flying puck. And where are you all

fellow players and opponents – the Čeglei brothers, Laco Valentín, Zdeno Píža,

Jano Frívald, Fero Kovačovský, etc. There were few girls living around, but our

contacts with them were not frequent: Lízinka Brabcová, Mireille Pipašová,

Jožina Bártová... We were all in love with Marianna Glatznerová, who used to

turn up from the nearby suburb of Krasňany.

In

my school at the time, I was in the same classroom with a few boys who played

junior ice-hockey competition for the local team called Slovan (Gábriš, Valach, Škoda, etc.). They came to Halatka for a match – only to be beaten by us. In

return we came to their indoor skating rink where it was us who was beaten. The

explanation resides in two kinds of ice: the outdoor ice is hard, the indoor

one is soft. Their skates were not sharp enough for our ice and could not be

controlled enough; our sharp skates could not be controlled on their ice

because they were cutting too deeply into their soft ice. On balance, they were

better players than us.

Sometime

later we had at Halatka junior ice-hockey team from nearby Raca, led by

eventual first-league players, the brothers Ölvecký.

Their ice being of the same quality as ours they had no problem with defeating

us.

In

our street there lived Emilo Klubal, ex-ŠK Bratislava (top league) player, and, towards the

end of his career playing for the local team. Much older from us he came and

played with us on occasions. His ability to keep the puck on his stick we could

not but admire, for it was impossible to take the puck from him!

As

to the family of Klubal: their father, and invalid from the first World War,

had a little hut in Dynamitka, opposite the Kasino, from where he was selling

tobacco, sweets and such; he died fairly early. They had 3 sons. Anti, an air

force pilot, perished under a tractor in a hangar in Presov; Franci (an ex-air

force pilot) died about 40-years old from cancer of stomach (and left behind a

beautiful wife with a small son); Emilo, mentioned afore, lived long. Married

to a one-handed engineer from Dynamitka; I am not aware of their children, if

they had any. Mrs. Klubal, somewhat out of her mind after all that misery, used

to stand on the footpath in front of their house, complaining with a

far-reaching voice to any passer-by.

Idle

time in summer was spent swimming and playing in Halatka. Our neighbour, a Mr.

Tomšík, fashioned a wooden boat for us, and we used it to navigate the entire

world, from one end of Halatka to the other. Halatka used to dry up in summer,

except for a few puddles in the deepest parts. It was time for finding old

pots, broken ice-hockey sticks, even desiccated carcasses of kittens or

puppies. Who knows where all the fish disappeared during such times, for as soon

as the water came back with the first rains Halatka was full of fish again.

Hobbies and speculations.

Having

learned how to use a microscope during studies at the Agricultural University

in Nitra, I discovered in Halatka a whole world of hitherto unnoticed marvellous

animals. With a magnifying glass, or with the ‘scope borrowed from the school I

spent many a summer day on the shore of Halatka, “immersed” in its water. Up to

this day I regard a simple wing of a mosquito with a mixture of admiration and

awe. From my flying days I know that a wing must have certain

aerodynamical curvature, certain “cleanliness”, and other properties. Mosquito

wing ignores all these requirements: it is completely flat, and instead of

“cleanliness” it is entirely covered on both sides by tiny thorns. And, as if

the thorns were not enough, there are various leaves, not unlike tiny oars, sticking from the edges; the mechanism of wing attachment to the body must be a marvel of design (too small for me to see even under the microscope)! Flying machines, invented by us, need three separate things for their function:

wing, control surfaces, and propulsion. The mosquito is happy with one, its

wing combines all three in one. Each one of the

above-mentioned parts – wing, thorns, oars together with the complicated joint between the wing and the body, is manufactured and

installed according to the plan, using tools, all stored in the mosquito’s egg.

Compared with such a wing, from engineering point of view, our most

sophisticated machines are but wet sandcastles (and not to mention other parts

of the mosquito body). The mosquitoes - apart from their function as feed for larger animals - are to us but unpleasant pests but owing to my

admiration of their engineering and quality of the construction I always hit

them only with a good deal of hesitance.

Note: after many years I read somewhere that the Portuguese poet de Bocage saw in the mosquito proof that the God exists.

It was there when I realised that life as a whole consists of the head, stomach and a gut, and which 'animal' keeps alive by endlessly (?) devouring products of its own body. I even tried to draw a picture of such an animal, but not being a Hieronymus Bosch, the cartoon has never materialised.

Unlike

us, mammals, insects have the hard parts of body on the surface, soft ones hidden

underneath. Under a microscope the sophistication of these hard parts becomes

obvious. From my many years spent in various design offices I know how many hours are needed to create each and every part; how many drawings must be created and

revised to comply with various requirements; how many times is every part

manufactured for experiments and matched with all surrounding parts until they

work together as dreamed up by some designer, engineer or an artist. And that’s

not the end of the process! The part, be it in the car, airplane, bicycle or a

TV set must be able to be mass-manufactured, must undergo hundreds of

tests – strength, resistance against environment, look, price, etc., and only

after all that (and certainly much more) can be released into “life”. As to mosquito,

how many “drawings”, hours of thinking, testing, matching, is hidden behind every

part of its body before it’s released into production – and who by? Where is

the design office, those engineers, draftsmen, drafting tables or computers?

From observing any insect’s body under a microscope it is impossible to believe

that it has all developed “by itself”...

The

fishpond Halatka decline began when, close to the railway bridge on Račianska

ulica, the Department of Police built a service workshop for the fleet of their

vehicles: in Halatka began to appear petrol, oil, suds of various colour,

bottles, oil rags, tins, and the fishpond gradually turned into a putrid swamp.

It disappeared with finality when it was decided to alter the radius of the

railway embankment towards Rača. The work began already during the war, but

fortunately it remained unfinished at the time. Today, apart from the railway

embankments, there are little gardens with sheds the size of a postal stamp.

Like

many people around us, we had in our backyard a couple of milk cows, a porker, poultry, geese, ducks, rabbits, bees, even a turkey. Even today, after more

than 70 years, I feel at home in the presence of a dog, cow, or a hen. Unlike

us, they remained the same: clothed the same way, speaking the same language

all over the world, with interests unchanged, and their culture and toys the

same. They do not crave tricycles, Meccano sets, books, wristwatches, plates,

furniture, and houses. They can read our thoughts to the extent that is

important to them, and we are in their eyes some sort of strange parasites,

something which we are indeed (as well as in relation to all other animals,

birds, fish an insect in the world).

Foodstuff.

Everything

I heard, saw and lived through tells me that the family was not only completely

self-sufficient as far as food is concerned, but it was able to sell a lot of

items, or exchange for items that were short of: depending on the season it was

fruit and vegetables, milk, cheeses, honey, poultry, eggs, bacon, sausages.

Such self-sufficiency was supported by the political system of the time. Nobody

discovered (yet) that by concentrating large-scale manufacture of foodstuff it

is possible to suck money from the population, use the money to buy cars,

build castles, buy beautiful women, smoke fat cigars, assist in altering the laws/politics/society to his liking and drink expensive

alcohols; and nobody thought of formulating laws to support such

transformation. If this sounds like something from J. J. Rousseau, or from old

Germanic ideals – so be it; connection with nature, with land and respect for

its fruit must always be the basis of every society, no matter how "advanced".

We

kept our animals, except for the cows, even after grandfather’s retirement.

Garden next to Halatka was a lot smaller, but, together with the vegie and

fruit garden around the house it produced enough for our animals, as well as

for the five of us. Later, there were even seven of us, when father and mother

joined us in the grandfather’s house, and auntie Helen got married and started

living with her husband. Food shortage began a year or two after the new

“communist” government assumed power in 1948. That government began a policy of

discouraging, even prohibiting, keeping animals for private consumption, as

well as production of animal food, and at the same time the food became on

short supply in the shops – what else could be expected! Suddenly, we had

shortage of food – from abundance to shortage.

The previous self-sufficiency was not limited to foodstuffs. Water for the garden came from

Halatka, water for the household was pumped from the ground. Fertiliser was

supplied in abundance by the backyard animals; phosphates, nitrogen,

potashes, DDTs, herbicides and similar stuff were still only words in textbooks

of chemistry. Grandmother used to genetically modify the poultry by selecting

eggs from the best layers for clucking-hens to sit on, and by selecting the

best rabbit-rams and rabbit-dames for breeding. Grandfather used to perform similar

modifications with the fruit trees, and with the best seeds for sowing. We had

no electricity – light was supplied by kerosene lamps. We had no radio, no

television, no computers; diners and evenings used to take place under the

kerosene lamps’ flickering light, and the corresponding shadows on the walls

used to paint pictures for me to accompany the words of discussions. For

heating we had timber from the garden, and coal and kerosene, supplied by the

railway as supplement to grandfather’s pension. The clothes were made by the

grandmother, and when the girls – my aunts – were old enough they used to make

their own.

Mother’s

tongue.

At

home, it was the language that came first to mouth: usually Slovakian mixed

with Czech, to please my mother and her Czech family; everybody from the

Slovakian side was fluent in Hungarian and German languages, that were used when

somebody came not knowing either Slovakian or Czech. Czech grandfather Havelka

could sing in Russian, or even speak, when he chanced upon some “brother from

the Russian campaign”, i. e. a Czech Legionary, still abundant in the country.

Grandfather and grandmother from the father’s side used plenty of dialect words

from Šal'a nad Vahom district. I was quite good in both Hungarian and German, on

my age level of proficiency, but did not progress much beyond that – those

languages were not popular after the 2nd world war, especially after

it became clear what those two nations did in countries they entered, uninvited.

Later the same fate befell the lovely Russian language we used to be force-fed

with from the time we were at primary schools. Books at home used to be in all

four languages, and when I learned a bit of Russian at school there appeared

books in Russian as well.

My parents.

My parents.

Father

used to translate cheap cowboy-and-Indians novels (called ro-do-kaps) from Hungarian to Slovakian. I

was always under the impression that he wrote and published a book, whether in

Slovakian or Czech. It is only an impression, for we had several of its copies

at home. It was mildly erotic, and it disappeared from the bookshelf when I was

observed as looking into it. The author’s name was a pen-name Karol A. Mária

(or Karel A. Marie), after father’s preferred Christian name Karol, and his

wife’s Marie. When he got a job at the publishing house by the name of Práca

(Labour), first as a proof-reader, eventually as an editor, we used to have

many a book with his name on them. The books were mostly various handbooks for

trade union organisers; his shiniest feather-in-the-cap was translation of the

so-called Law of Labour from Czech into Slovakian, followed by editing and

preparation for publication. With that I used to help him, a few pages here and

a few there. I did not last for long, the work was insanely boring (the same as

this translation of mine!). And I have always had a sneaking suspicion that the

famous Law of Labour smelt of some sort of criminality – it even stepped on my

tail later, see the chapter called Dynamitka. Father liked working outside in

the garden, and I once took a photo of him in that activity:

Below is the back page of a book he translated from Czech to Slovak language, and prepared for publication:

He

was a good person, reluctant to show his emotions; I felt, however, his immense

love towards me. He was helping me wherever he could, but always invisibly, so

that I mostly did not know where the help was coming from; one such occasion is

mentioned in the chapter Dynamitka. Our personal relationship was ambiguous:

like most of the self-centered sons I was unable to find a path to him, despite

a number of similar interests, and that’s how we parted in 1995 for the last time in

Prague, where he lived with my sister and her husband. We parted by a mere

handshake, and it did not occur to me to embrace him, kiss his 83-years old

cheeks and thank him for life and love – I have tears in my eyes now as I am

writing (and translating) this. I left for my faraway home, and a year later he

died after a bout of 'flu, quietly, the same way he lived his life ("melted into the blue yonder", to quote his favourite words) ...

Father

and mother had their wedding at the railway house in 1935; they met a mere few

months earlier in the then popular garden winery belonging to the family of

Rajt that used to be just past the railway bridge towards Račišdorf, on the

left side of the road. The mother came from the direction of the Czech “colony”

around Biely kríž with her girlfriend Juci. Father, after the long period of

unemployment just landed a job as a taxation clerk, and was able to show off a

bit in front of the girls:

|

| Havelka family, Christmas 1935 in Bratislava. L-r: Gustav, Julie, Josef, Otka, Robert Nedvěd, Krasava Nedvedova, Marie, Otka Skrabova. |

Oft-repeated

cliché that the Czechs were settling in Slovakia because of shortage of suitably

qualified people was not applicable in the case of our families.

My Czech grandfather Josef Havelka

was barber by trade and during the first world war spent 4 years as a soldier in Czechoslovak Legions in Russia, travelling from Poland to Vladivostok; his typewritten description of his travails called Anabase is still in my proud possession. He played a few musical instruments well, and in the Legions, as well as at the Main Station in Bratislava, he was one of the co-organisers of orchestras. Here he is, in the top row, second from left (picture taken about 1930):

In

relation to the railways, and in comparison with the other grandfather,

Hatvani, he did not know much. Same as grandfather Havelka, grandfather Hatvani

spent 4 years in the Austrian army, worked all his life around the railways,

and was fluent in Slovakian, Hungarian and German languages, including all the

local dialects. Grandfather Havelka spoke Czech, German and Russian. Most of

the railway employees in Slovakia at the time being Hungarian speakers,

grandfather Hatvani would have been much more suitable pay clerk than

grandfather Havelka, if there was a shortage of such clerks. Ah, well, those

were the times: the new Czechoslovakian government was struggling to employ the

multitude of citizens returning from all corners of the world after the 1st

World War, and suddenly there were territories freshly vacated by Hungarian

speakers, who preferred to live in the newly created Hungary...

Grandfather

Hatvani let it be known occasionally that after the fall of Austro-Hungarian

empire Bratislava district should have been incorporated into the city of

Vienna, rather than into the newly created Czechoslovakia – obviously, he felt

closer affinity with the Austrians than with the Czechs. 50 years later I found

similar statement in the memoirs of Michal Bodický (1852-1935, a Slovakian

protestant priest), to the effect, that he always felt good crossing Morava

river, which formed border between Slovakia and Austria, in the direction from

S. to A. (i.e. from the oppressive Hungarian system into the liberal Austrian one).

I can wholeheartedly concur, for I felt exactly the same, even on the same spot!, albeit for different

reasons (i. e. from “communism” to democracy).

The

Havelkas had three children, of which my mother was the youngest. All three of

them married in Bratislava: Gustav with the local “Pressburg” girl, Otka with a

Czech lad from Bakov nad Jizerou, and my mother with a Slovakian lad. In the picture below they

are in their flat some time in 1927 (the violin and viola in their hands are in

my possession to this day):

My Czech family in about 1928.

Top l-r: ??, Julie Havelková nee Škrábová, Adolf Havelka, Anna Havelková nee ??, Emilie Nechanická nee Havelková, Josef Nechanický, Josef Havelka, Gustav Škrába, Aněžka Škrábová nee ??.

Bottom l-r: Otka Havelková (later Nedvědová and Stará), ??, Gustav Havelka, Otka Škrábová (later Štěpková), Marie Havelková (later Hatvaniová)

Early childhood memories.

In

the railway station house, as the first grandson, I was absolutely everything until my

fourth year, when, in 1940, the grandfather retired and the entire family moved

into newly purchased house on Račianska ulica 794, opposite the inn called U

Dudáša. Our old house was taken by family Trtol, our friends, also railway

employees. Here is Karol Hatvani with his wife Júlia and daughter Ruženka in their backyard, in about 1938 (the dog's name was Rigó):

From

the railway house I treasure a thousand little child’s memories: the animals, the

bees, ducklings, the cow who acted maternally towards me (god knows how they

behaved each to the other with my real mum), the visits of my Czech family,

various distant aunts, cousins and such – all Hungarian speaking – from Šal'a

nad Vahom district (Szőke, Szépbőze, Andódy); the slaughter of pigs, oranges on

the Christmas tree, the dainties (lepéňs, kuglufs, gerhenes, boiled plum balls,

morváňs and hajtováňs) of my Slovakian-Hungarian grandmother – well, it was

paradise on earth!

Comparing

lifestyle of my Slovakian grandparents with the lifestyle of an average family

today (2011) I can’t omit a few little details. I am leaving to various

professionals to evaluate social and financial differences.

In

my common sense thinking it seems to me that the personal ability, practical

knowledge and subsequent quality of life of those grandparents were far above

lifestyle quality of the average family today. That family, with its near-total

dependency on two incomes, living in blocks of flats with limited access to the

nature, dependency on financial institutions, reduced status of parenthood, and

limited range of qualifications and abilities seems to be closer to the

gone-long-ago serfdom, compared with the nearly free life of my grandparents.

By the way, in those long-ago days, the tax rate was flat 10%! Imagine the joy

today!! Less welcome would be physical punishment common in those days, and the

quirks of the local nobility, many of whom had a few bats in the belfry from

the abundance of good life (countess Elisabeth Batory, the most prolific murderer in history, lived in the present-day Slovakia). Essential upbringing of children in those days was

taking place at home, with father, mother, with siblings and animals, in the

kitchen, backyard and in the neighbour’s places. School was regarded as good to

teach reading, writing and arithmetic, a bit of glimpse into the latest

cultural happenings, and through religion to absorb a little of higher learning.

As

a married couple, with four children, their main source of income was

grandfather’s salary as railway employee (signalman, point’s operator). On the

side, they used to sell products of the land they were permitted to use by the

railway: bacon, sausages, honey, butter, cheese, fruit and such. The products

were displayed on a table that stood in their front yard, next to the road to

Dynamitka (a large chemical factory nearby); tram terminal station was also in

front of their table, so there was no shortage of customers. Alongside the

railway salary they had free use of the house with large garden and stables,

also coal for heating and kerosene for lighting. Also at their disposal was a

strip of land 50 x 400 metres – of fairly low quality – along the railway line. Grandmother

worked at home. Both grandparents had but basic school education, 2 or 3 years

of primary school. Grandfather acquired some knowledge around railways during

his 4 years long compulsory military service in the telegraph/railway unit in

Korneuburg, near Vienna, Austria; grandmother, in her youth, worked for a few

years as a maidservant in the Esterházy palace in Galanta.

The

scope of their practical abilities, and associated theories, was far exceeding

similar scope of contemporary marriage couples’. Grandfather, apart from his

work as a railwayman, cultivated his allocated strip of land. He knew how to cultivate, what to plant and when, how to

harvest/store/process, etc. He knew how to take care of all domestic animals,

he knew how to kill them, butcher, process, store, etc. He was an amateur

apiarist; was able to do all the jobs around maintenance of the house and sheds,

various machines around the house and in the field; he used to make various

kinds of wines depending on the seasonality of the fruits, from grape wine down

to bread wine. He knew what how to cure or heal the animals. Of that I remember

one of his stories: on one occasion he took carcasses of two pigs, which died

of a swine virus, to a common dump in the fields. A few days later gipsies from

the district unearthed the carcasses and enjoyed a several days long party there.

His

wife, my grandmother, was the boss of the house, cooking, bread baking, making

preserves depending on the season, sewing, washing, mending, and taking care of

children of all ages. Like her husband she knew how to kill a small animal,

how to clean it, butcher it and prepare it for dinner. She was milking the

cows, making butter and cheeses; she run a small herb and flower garden; when required she helped

with field work; she ran the display table in front of the house, with produce

for sale; when necessary, for instance when the husband was down sick, she did a

lot of work at the railway, such as manning the barriers, maintain and installing

kerosene lamps for railway signals, and such. Once every couple of years she

painted the house from inside with (calcium based) paints, as high as she could

reach.

They

had two assistants, for as long as they were able – grandfather’s mother called

Rozália (Rozanenna) Oláhová/Hatvaniová/Vicenová, and grandmother’s mother also called Rozanenna

Maczkiová, who both lived in the same house. Towards the end of their lives, they remained in the care of my grandfather and grandmother. Below is the

picture of grandmother’s mother (Oláhová). According to Ruženka, my aunt, she loved to

sit in the garden after dark, watching the moon and the stars:

A little

remark concerning the genetic modifications as performed by my grandparents.

Domestic

animals, insects, also plants suitable for agriculture, fruit trees,

etc., have been discovered and developed for use by humankind by exactly these

humble grandfathers and grandmothers. I am unable to think of ONE animal, ONE

plant, developed for common use by an institution with a galaxy of Nobel prices

and Patents after its hallowed name. DDTs, herbicides, phosphates and such,

yes! Presently in-vogue genetic modifications seem to be aimed at the exclusion

of these grandfathers and grandmothers from the ancient process, and are mainly

aimed at maximising profits to institutions, and in not the last order, at

cheaper destruction of imaginary enemies.

After

us,

the land by the Halatka fishpond has been subdivided into a number of gardens that have been leased to retired railwaymen. My grandfather was allocated a garden about 30 x 60 metres, backing to Halatka. For many years we used it for growing vegetables and fruit, for swimming in Halatka, for days of leisure, until, around 1963-4 there appeared bulldozers and put an end to the Gardens of Paradise and to Halatka as well.

the land by the Halatka fishpond has been subdivided into a number of gardens that have been leased to retired railwaymen. My grandfather was allocated a garden about 30 x 60 metres, backing to Halatka. For many years we used it for growing vegetables and fruit, for swimming in Halatka, for days of leisure, until, around 1963-4 there appeared bulldozers and put an end to the Gardens of Paradise and to Halatka as well.

When

I was about 4, I remember walking with grandfather to admire a house just being

completed by a Mr. Andrášek. And one lovely spring day in 1941 we moved in, and

I was helping auntie Ruženka with polishing the floor using a nice aromatic

block of beeswax. Račianska ulica, photographed from that house in 1951 looked

like this (to the right from the bus stop is a path called Novy záhon since

2011). The alarm siren, mentioned above, is visible next to the house on the

right; to the left of the siren is Bratislava Castle, barely visible:

And this is how it looked in the opposite direction (behind the Ruckriegel/Sloboda house in the distance is today’s Pekná cesta; HBV/Krasňany did not exist yet. Our house is second from left:

Traffic used to be fairly busy: for example, a bicycle can be seen in the distance in the above picture (“be careful, little Charlie, if he happens to be drunk he can run into you!”, was the grandmother’s admonishment)...

And this is how it looked in the opposite direction (behind the Ruckriegel/Sloboda house in the distance is today’s Pekná cesta; HBV/Krasňany did not exist yet. Our house is second from left:

Traffic used to be fairly busy: for example, a bicycle can be seen in the distance in the above picture (“be careful, little Charlie, if he happens to be drunk he can run into you!”, was the grandmother’s admonishment)...

After

their wedding my parents rented half of a house on Kukučínova street (from

where I was carried – unborn – by my mother to maternity hospital on Zochova

street, some 3km away), then they moved to Légiodomy, then to a house called Fričák on

Račišdorfská street, then to a rented half of a house nearby, and, finally, to

a one bedroom flat in Nová doba 3, all of it within 2-3 years’ time. As for

myself, I lived in those flats, and have but dim recollections of the first few of

them, but I always preferred being with my grandparents and with their

daughters, my aunties Helen and Ruženka. And especially, I liked the gardens

and the animals. In Nová doba I suffered from a few bouts of middle ear infection,

until, when I was about 5, my mother took me by tram for an operation in Štátna

nemocnica (Dr. Kretschmer); to this day I am sporting a deep scar behind my left

ear. And I can hear to this day my mother’s sharp admonishment “you would be

better dead!”, when I was crying and howling from pain – the antibiotics being

still many years in the future...

My

father was my grandparents’ only son, his older brother having been killed as a

steam train driver in 1933, somewhere near Čeklís. My aunts remarked on occasions (with not a small hint of malice) that my parents changed their address so

often because of my mother’s fondness of a good argument with the neighbours. Many,

many years later, with auntie Ruženka, we were discussing one character from

the popular book of Asterix, namely somebody who is able to start argument with

anybody at the drop of a hat. That character was sent by Julius Caesar in an

attempt to start arguments among the unruly Gauls. Ruženka suddenly remarked

that this character is “exactly the same as your mother!”, who at the time had

been in her Czech paradise for at least 15 years – may the Czech god, mummy,

give you his eternal glory, and plenty of neighbours for many a good and juicy

argument...

An old family friend Betka

Nemcová/Brabcová objected to my description of my mother. According to Betka my

mother was exceptionally merry and friendly person, and she always talked about

me in the best of terms.

I

said above “in her Czech paradise” on purpose, for my mother, despite living in

Slovakia since grade 4 of primary school (“teachers were all Czechs”), could

not speak Slovakian, and used to look at the Slovakians down her nose,

including my father, and, probably, myself as well. There lived many Czechs in

Bratislava at the time, and whenever we stopped in the street for a talk with

somebody, that somebody always happened to be a Czech; we used to visit many

people – they were always Czechs, be it around Nová doba estate, where we

lived, or on Račianska ulica, where the grandparents lived. My mastery of Czech

language was the same as hers, but, politically at the time, there was push

for “Slovakian language in Slovakia”; during various visits of family in the

“Protektorat”, as the Czech lands were known at the time, I spoke Czech. As it had

always taken me a few weeks to slip into the local dialect, I used to be known

as “that stupid Slovakian” – remember still, boys from Humpolec? That term of

endearment did not last long, for, towards the end of our two months I spoke

the same as everybody else. Also, I used to be stronger that most the boys of

my age group, and because of my dislike of fights I always ran away wherever

possible (I was unlucky on a few occasions, when I was unable to escape, I usually unintentionally managed to hurt somebody pretty badly - torn ear on one occasion, broken nose on another, etc. And guess who was the baddie then?). And back in Slovakia I was suspected of being a Czech...

The

original text until now has been in the Slovakian language. The following text

was in the Czech language.

Humpolec.

Until I was about 15 we were

spending 2 months of summer holidays every year in Humpolec. We lived with my

Czech grandparents in their ground floor flat Na Kasárnech, opposite the

factory J. F. Jokl. When grandfather died in 1947, grandmother moved into a

small house owned by her brother Gustav Škrába at No. 945, Nerudova ulice.

Relatives in Humpolec were aplenty at the time: great-grandfather Adolf Havelka

lived on Lnářská ulice (with a married couple called Vacek), in a flat above

the bakery of Vilém Drbal lived uncle Pepa and aunt Emilka Nechanická, uncle

Gustav Havelka lived on Sluníčkova ulice with his pretty wife Anda. Down the

hill lived uncle Gustav Škrába, his wife Aněžka, their daughter Otka (a pretty

woman) with her husband Franta Štěpek; with their son Luboš, his wife Libka

(née Pejšková) and their entire family I am still in touch.

I used to play with the boys

around Na Kasárnech, with Jarda Vazac, Karel Suchý, Trnka; at Nerudova ulice it

was Franta Dušek, brothers Kubíček, mainly Olda. And others, as they came, from

the entire town: Olda Městek, Kordovský, Balcar, Hůla, Kulík, etc. With many a boy I worked at various holiday

jobs, especially at the JZD (Agricultural cooperative) at Nerudova ulice,

opposite the road to Jirice (the supervisor there was diminutive Mr. Vrána). We

used to work on the harvest from the fields above Nerudova ulice (no blocks of

flats there yet), we cranked the winnowing machine, making sheafs from freshly

mowed cannabis (industrial variety) next to the road to Trucbába, and other

jobs. And there were pretty girls: cousin Krasava and her friends (Jarka Kvášová),

exceedingly pretty Božka Šimková, the Kostkuba girls, Jarka Holubová, Marjána

Vaňhová, Růženka Kubínová. Being 12-16, each one of them is etched in my

memory, and remains there to this day, when I am over 70... Through cousin Jarda

Nechanický I knew Honza Příborský and Květa Mazáková. And through the same

Jarda I played tennis at the courts next to Cihelna fishpond, but the names

from there have escaped from my memory.

Those

friendships were rather ephemeral. It takes a while for the child to establish

friendship, and when it was all underway I was on my way home. There were

difficulties with the language. I was fluent in Czech, however, the local

accent during the ten months long absence evaporated and I had to start anew

again.

Grandfather

Havelka, an ex-legionary during the first world war, had plenty of interesting

books in his bookshelf. I read their books about the “anabasis” of the

Czechoslovakian legionnaires in Russia, books of Švejk bound in yellow

(together with supplement by Vaněk), Thousand and one nights, Brehm’s Life of

animals, Russian fairytales in Czech translation, and plenty others.

Grandfather had bound magazines popular at the time (Výběr and Zdroj), with

plenty of interesting stories written inside. Grandfather was an avid musician,

and to this day I keep two of his instruments, a violin by Stainer of Absam, and

a viola with sticker Stradivari inside (a replica, some 110 years old). His

wife “bába” Havelková, was an avid mushroom gatherer, and she used to lead

all-day expeditions here to Brunka, there to Trucbába and beyond, as far as Želiv. I liked her cooking, and have fond memories of her mushroom soups,

sauces and omelettes, blueberries cakes, etc.

Great-grandfather

Havelka wrote memories of his working life, and they have been kindly published

in the internet pages of the district paper Humpolák under the name Soukenictví

v Humpolci (Fabric making in Humpolec).

And

what happened to my Humpolec family? All gone! And every few years I pay them a

visit - at the local cemetery...

Schools.

My school years began at primary school at Vajnorská ulica, near tennis stadium. On the ‘photo below I am the blond boy above the teacher/principal Mr. Vagner. The girl with the bow between us two is Anka Duchoňová, with whom I was at various schools from the beginning to the end of secondary schools:

All

are familiar to me, but I don’t remember all the names here: top row middle is

Chorvát, next to him dusky Kovačič (take care, like many whose surname ended with a "č", he’s a fighter!), blond Tóno

Mišík (good boy, with beautiful parents), and diminutive Pongrác (a wild

fighter, possibly with a few bats in his belfry!); underneath from

left Milan Jergel', Milan Dobrotka, Cimra, Ďurček; and in the bottom row I

remember only Edo “Ficko” Gábriš (3rd from left), and Julka

Duchoňová (sitting right of Mr. Vagner).

To

that school I went from the flat in Nová doba estate where my parents lived.

However, since I kept gravitating towards Račianska ulica, where my

grandparents lived, from Grade 2 I was in the primary school at Dynamitka. The

principal was a kindly old Mr. Vojtek, with occasional appearance of his son as

well. The teachers were Mrs. Vančeková and Mrs. Hermanová, both rather tough

and strict ladies. Towards the end there was (allegedly) a recent guerrilla

fighter Ján Ďurové ("The cross-eyed apostle”, for he, indeed, was cross-eyed, and

had a beard, an unusual thing at the time). There were plenty of religion

hours, taught by a priest from the nearby church. Interestingly, I have no

recollection of him whatsoever, despite my occasional assistance at the altar,

and despite me carrying some religious flag or insignia during the annual

religious street procession.

War

years.

The

War in our family started quietly, at least from the perspective of my 4 years.

At first, it was the relatives from the district of Šal'a nad Váhom, all

Hungarian speakers, who disappeared; Šal'a during the war “went” to Hungary. During

the madness of 1940, when the Czechs were expelled, the whole of our Czech

family disappeared as well: the grandfather, grandmother, uncle Gustav and

auntie Otka, leaving behind various wrecks: Gustav left behind his wife, native

from “old” Bratislava by the name of Hansi. She found herself helpless in the

small-town Humpolec’ finely honed gossipy atmosphere; Otka left behind her

husband “Róba” (Robert Nedvěd), who, immediately after the cancelled

mobilisation fled via Poland to Great Britain and perished in landmine blast

near Dunkerque in March 1945 (his name appears on the memorial plaque at

Dunkerque); and, finally, Helena, Gustav’s daughter, my cousin. My mother was

trying to leave with them but succumbed to my father’s insistence. The entire Czech

family did not have to leave, providing they accepted the new Slovakian

citizenship; unwisely, they preferred the “Protektorat” citizenship, as the

Czech state became known under the German occupation.

And

the props keep being re-shuffled: suddenly, the nearby lovely Austria became

Germany, and Mr. Hitler with his armies turned up under Bratislava, only 300

metres across the river Danube. Hungary, Hitler’s lap dog, crept up to the southern

outskirts, somewhere near Podunajské Biskupice, even Račišdorf belonged to them

for a few days! In the streets were marching the newly created Home guard, also

platoons of soldiers in the uniforms of new Slovakian army. The air was thick

with the dangerous looking biplane fighters, short and snub-nosed, at night

illuminated by search lights from Kuchajda, but otherwise it was all quiet – at

least where we were. Auntie Helen, managing director’s secretary at Dynamitka, used

to bring from work copies of German pictorial magazines called Signal, with

descriptions of the glorious achievements of the German army, be it in the

Ukraine, deep in Russia, Africa, at the Caucasus, even on the Crimea. Those who

were a bit wiser knew even then (1940-41) that all that outstretching is the

beginning of the end, and not of glory! So much territory, with not exactly

friendly inhabitants, is impossible to keep together from one central point:

sooner or later, somebody would start chopping all those tentacles off... My

geography lessons started on the exciting pages of those Signals.

Living

a few hundred metres from the main railway line from Bratislava to the east we

were able to see goods train full of cannons, tanks, trucks and other military

machinery – heading east. In some of the carriages were either Slovakian, or German

soldiers, who used to yell at us, children, and would throw to us packets of

biscuits, lollies, even chocolate. Other German soldiers used to sit or hobble,

variously twisted, without legs, without hands, on crutches, around hospitals.

There

were more German soldiers in the Protektorát (as the Czech lands used to be

called under German occupation), where we used to spend school holidays with my

mother. They marched in the streets, hang around the pubs, controlled traffic

at intersections, and were checking the trains on the border between Slovakia

and the “Protektorát”. Place and street names were bi-lingual, German name

(written in schwabach) usually first, Czech name second. There was food

shortage in the “Protektorát”. During each of the yearly trip from Bratislava

to Humpolec with my mother we hauled a heavy suitcase, full of food. Stuck

deepest in my memory is one suitcase full of potatoes (and Humpolec district is

predominantly potato area!). The windows at night had to be blocked so that no

light could escape. Some stations on the radio were banned, which decree was

ignored by my grandparents. To this day I can hear the boom boom boom booooom

of kettle drums preceding the Czech transmission from London. Listening to the

“western” radio stations was banned on the pain of death – how easy it was for

me, as a child to blab somewhere...

Alarm

sirens were installed in Bratislava to warn the population of the air raids. On

our street, one of those sirens appeared opposite house No. 140. It was some

300 metres from our house, but the sound of it was deafening, nevertheless. At

the same time, on the water tower in Dynamitka, a large roundish basket was

displayed. According to its position on the mast, and maybe according to its

shape as well, it signified whether or not the bombers are heading towards us.

The

air raids started, and the main target was nearby Vienna. Usually, we could hear

undulating deep hum from the direction of Šamorín, eventually we could see

silvery dots trailing streams of vapor; when they came closer, we were able to

see 4-engine airplanes, heading towards Pezinok, where they slowly turned left

and disappeared beyond the mountains above Račišdorf. Bratislava itself

suffered but little: oil refinery Apollo, next to the only bridge over river Danube, for obvious reason – oil thirsty Germany was just across the bridge.

Some bombs fell on the lower end of Štefánikova ulica, also Krížna ulica, and I

saw a few craters in the Emiház fields behind the railway line opposite to where Mladá

garda is today. And Rendez: it was bombed by dark looking twin-engine airplanes,

diving very low, maybe 100 metres, from the direction of Sv. Jur. Once in

Hochštetno in summer 1944, where we slept in the long house typical for the

agricultural regions, next to the river Morava, the house belonging to Lénard Ščepán. We were playing on the sandy playground by the name of Kozliská, when,

suddenly, from behind the nearby low knoll flew groups of very large airplanes,

flying at almost ground level, heading towards Vienna, from which direction we

could hear the dark sound of continuous explosions, and saw clouds of dark

smoke rising to the sky. Probably on the same day one of the airplanes released

a number of bombs a few hundred metres from us, which, unexploded, were partly

sticking from the mud next to river Morava – and we, kids, were playing among them the next day...

On

the plain of Kuchajda in Bratislava we saw cannons shooting at the airplanes.

There were multicoloured clouds of smoke in the sky from the exploding

projectiles. We saw huge pall of black smoke rising from the bombed refinery

Apollo. A few weeks late a neighbour, Mr. Petrík, turned up on the street bandaged

from top to bottom – he worked in that Apollo during the raid. Otherwise, the

bombing avoided our immediate surroundings. The most unpleasant was watching

the bombing of Rendez, some 2-3 kilometres from our house. A few bombs during

that raid fell on some house in Račišdorf, a few in the vicinity of Žabací

majer. And again, a few days later we, kids, were playing in the fresh craters,

and the smashed steam engines...

War’s end.

Sometime

around 1942-43 there appeared on our kitchen table a miracle – a crystal radio.

It was a wooden box sporting two Bakelite buttons on the front, and a glass

tube with little lever on the side. There was a silvery crystal in the tube,

and the lever moved a thin piece of wire around that crystal. Upon that wire

touching the crystal on the right spot a voice could be heard, or music. The

whole family sat around the box and vied for the headphones; the neighbours

came to look! Auntie Helen was not impressed by all the excitement, and she,

about a year later, brought from work a real radio! It was a small box marked

Philips, and, unlike on the crystal radio, it was possible to tune in to

various stations. Headphones were not needed the radio could be heard as far

as the street some 25 metres away...

Through

that radio I became familiar with the names in the Slovakian politics of the

day: Jozef Tiso, Tuka Béla, Lednár, Čatloš, Ďurčanský, Tido J. Gašpar, Šano Mach,

Konštantín Čulen (“we don’t want nothing but what belongs to us”, he used to

say), and, of course, with the names from abroad: Hitler Stalin, Horthy,

Mussolini, Roosevelt, Churchill and others. Hitler, Mussolini, Horthy and

others were on our side; Stalin, Roosevelt, Churchill and other were the

enemies.

I discovered a film clip from a military parade in Bratislava in 1944 Vojenská prehliadka v Bratislave pri príležitosti 5. výročia vzniku Slovenského štátu (14.3.1944) - YouTube

My parents lived in the block of flats opposite the grandstand (where the President of Slovakia, Dr. Jozef Tiso, stands and greets the soldiers). When the grandstand was being built a few days previously I, with a few of my friends, used to play on and around it. During the Parade we were under it for a while until chased away by some policemen. Of the parade I remember only the airplanes, for I was unable to see the road between the legs of the onlookers (I was 8 years old at the time).

Once,

with auntie Helen at the upper end of Štefánikova ulica, we heard about the

death of president Roosevelt. “That’s good”, I said, for Roosevelt was the

enemy. I received a sharp rebuke from Helen: “Thou shall NOT rejoice when a

human being dies, not even when he is the enemy!”.

News

slowly started appearing about the heroic German army “elastically disengaging

from the enemy” (that is, retreating); how the heroic marshal Rommel

single-handedly pushes back his berserked enemies; cartoons of Stalin pulling the

ship of state in Volga full of blood; caricatures of Jews with big noses

reaching into our pockets to get our money (which became reality a few years

later. The “Jews” in that case were Russians with their local lick-spitters).

At the school on the wall there were portraits of Doctor Josef Tiso (Slovakian

president), with Adolf Hitler. In the local radio transmission, a strange voice

could be heard – a pirate transmission. News on the radio began to be

accompanied by loud music, to drown the pirates. Apparently, the war was coming

closer to us. There were news about the Allies in Normandy, fights in the

Ukraine, about cowardly bombing of the civilian population of Berlin (bombing

of London by the Germans few years previously was heroic!) ... Civil defence

became one of the topics, and you could buy in the streets white badges of WHW

(Winter Help Something): great expectations were hanging in the air.

In

our street, Račišdorfská ulica, holes were drilled under the railway bridge,

and filled with explosives. These were interconnected by means of strings, and

one day we, the boys, pinched the strings and played with them – they burned

nicely, from one end to the other. I was able to see remnants of those holes during my last visit there in

2007. Erected next to the bridge were two concrete blocks, one on each side, as

an eventual obstacle for motor vehicles. Also, behind the fuel pump near

Krasnany there was a small cannon, manned by a lively German soldier. He even

shot from that cannon once or twice towards Žabací majer, for the amusement of

us kids. Similar cannon was located at the merger of the two railways, one from

Nové Zámky, the other from Trnava.

Germans and Russians.

Around

Easter 1945 the grandfather decided that staying close to the main road could

become unpleasant and the whole family (himself, grandmother, me and the

two aunties) moved to the cellar of the second forester’s house (Pechan) above

Schienweg. After about a day or two there I was playing outside when, suddenly,

from downhills on the road emerged a few German officers on horseback,

followed by hundreds and hundreds of German soldiers. Among the soldiers were

wagons pulled by horses, and all of them, soldiers and horses, looked dead

tired. The officers on horseback pulled to the forester’s house’s yard to

water the horses. They told us that they are being followed by the Russians,

and that we have never seen such a wild mob as them. They left – and it was for

the last time that I saw a German soldier. Generally speaking, I have no bad

memories of them, either from Humpolec, where there were lots of them, or from

Bratislava, with very few. Once, on the street not far from our house, I walked in opposite direction to a lone German soldier. I shot my arm up and said

“Hailhitla”, in the best imitation of the compulsory German greeting of the time. He did

not reply in kind but growled instead in some kind of Viennese-Bavarian

dialect “Geh’ weg’ nach Oasch, búbi (to an arsehole with you, nipper)”!

As

to that “wild mob”, mine and my family’s experience with them were the same as

described many times elsewhere: Russian soldiers murdered German soldiers

without hesitation anywhere they found them, thus earning reputation of

cold-blooded murderers; they liked getting drunk – like pigs, as the people

used to say; they took and stole anything that caught their fancy, especially

wristwatches, jewellery, bicycles; they raped anything regardless of looks and

age; they did not understand the difference between toilets and bathrooms; they

did not like fences between houses – ruling class, they used to say. One officer slept and ate with us in our house for a few days. One evening he demanded my grandmother to make some scrambled eggs for him. He became infuriated to hear that there were no "yayka" (eggs) in the house, the hens having disappeared while the Russian soldiers stayed in the house a few days previously. He threatened the grandmother with his pistol, but in the end, he stormed out. After a while he returned victorious with a basket full of eggs and a bottle of some alcohol. The scrambled eggs we were forced to eat with him, and for my efforts I had to drink a "stakanchok" (small glass) of the alcohol called Griotka - it was quite tasty. A song

used to circulate, sang to the tune of the then-popular Lily Marlene: “The

Germans have left, the Russian have come, each of them yelling give me your wristwatch.

And when I was unwilling, they pulled their automatic weapon and “gimme,

fuckyourmother, gimme, fuckyourmother”...

At Halatka fishpond a couple of Russian soldiers on a few occasions tossed a hand-grenade into the water. After the mighty explosion we, the kids, were sent to the water to collect the stunned fish floating belly-up on the surface, into a rusty bucket. That bucket, full of fish, with some fishpond water in it, was put on top of a fire and the boiled content was then devoured by the two soldiers. Friendly offers to join in were declined by us...

On one occasion a platoon of Russian soldiers was marching past, three abreast, men and women. When they saw the fishpond some 80 metres away they spontaneously turned towards it, started running, tearing their clothes off as they ran. By the time they reached the edge they were all naked, or almost naked, and dove in with tremendous noise and general exclamations of mirth.

A

day or two after we saw the last of the Germans leaving I was with the grandfather in a house on the edge of

vineyards when somebody yelled “The Russians are coming!”. We all hid in the

house and waited. In a short while a soldier appeared in the doorway with hand

grenade in his hand: “German?!”, he yelled. Grandfather rose to his feet and

said that there are no Germans here, only civilians, women and children. The

Russian turned around, went to the front yard, grandfather and me behind

him, and the Russian tossed the hand grenade far into the vineyards. It did not

explode, and we were told to avoid the spot (I obligingly took off to bring it

back, but, fortunately, I was stopped in my tracks by grandfather and the Russian). The Russian

spoke with language we were able to understand a little.

The

war for us ended on a quiet note. We heard a few shots from the hills above

Račišdorf, otherwise nothing – German soldiers from our district vanished a day

or two before the Russian army arrival. I have no recollection of any Slovakian

soldiers from those days.

In

that house there was with us a man, a barber by trade, who the next day decided

to go down to his house, to see what is going on and perhaps bring his tools

and start working. He did not get far for he was found a few hundred metres from

the house we were in – shot dead. He was buried on the righthand side of

Schienweg, where the sharp rise gives way to almost horizontal road, and the

local stonemason, Mr. Čeglei, made him a nice monument. I have seen the grave

in 2007, but not the gravestone, with the words Antonín Kopal, April, 1945...

N.b. Many years later I was contacted by two men from the nearby Krasnany, who read the above paragraph in the slovakian version of this blog: what else could I impart to them about Kopal, for they were preparing to restore the gravestone. After lengthy exchange of emails, the gravestone was restored, only to be demolished a few years later by the owner of an adjacent land, and the two aforementioned men inserted a memorial plague in the wall of a nearby cemetery in Raca.

My personal experience in a similar situation.

N.b. Many years later I was contacted by two men from the nearby Krasnany, who read the above paragraph in the slovakian version of this blog: what else could I impart to them about Kopal, for they were preparing to restore the gravestone. After lengthy exchange of emails, the gravestone was restored, only to be demolished a few years later by the owner of an adjacent land, and the two aforementioned men inserted a memorial plague in the wall of a nearby cemetery in Raca.

My personal experience in a similar situation.

When the Soviet army invaded

Czechoslovakia in 1968 we lived in a ground floor flat in Bratislava, Hečkova

8. At night we could hear jet airplanes, and in the morning, we saw tanks on the

nearby main road – dozens and dozens of tanks, heading towards the centre of

the city. At lunch time I was starting my afternoon shift at the nearby

airport and decided to walk (instead of using the public transport, as usual). Deep in thoughts, I was about halfway between the

lake Zlaté piesky and the airport, when, getting to the top of a small

undulation, I was stopped in my track by a sharp “Stop!!”, in Russian language.

About 20 metres in front of me there stood a Russian soldier, with his

automatic weapon aimed at me. “Where are you going?”, he yelled in Russian. I

replied that I work at the airport. “Turn around and go back!!” Oh, yes, and you,

prick, would shoot me in the back, I thought momentarily. My Russian at the time

being quite good I started pleading with him. Short exchange ensued, during which the soldier cocked menacingly his weapon and shook it toward me, and then I

saw an officer coming towards us from behind the soldier. After a brief

interrogation I was allowed to proceed to work. And thus, I know exactly how Antonín

Kopal felt in the last few minutes of his life...

In April 1945, we

returned home after a few days in the nearby forest. Our house, now empty, must have been occupied

by soldiers, because everything inside was upside down, including the freshly collapsed sheds. Animals housed in the backyard were all gone (2 young pigs, a dozen of hens, six rabbits, one dog). On the

windowsill there stood a row of empty perfume bottles, belonging to my aunts.

The lively German soldier I found about 200 metres towards Račišdorf from our

house, shot, with a number of bloody holes in his chest. People were saying

that when the Russians came across him, they ordered him to walk from the

footpath across the road towards the fields, and when he was about 20 metres

away, they shot him – can you imagine his suffering during those 20 metres? With

grandfather we put him in a wheelbarrow and buried him in the field behind the

near railway bridge. In his pocket we found a small badge of greyish metal,

which grandfather kept in his drawer at home. A few months later the body was

retrieved from the grave and re-buried in a grave together with all other Germans

found around the city (God only knows where that grave is).

My

aunt Mariška Andódyová, who lived in the field next to the railway near Prievoz

had similar experience. There was the same small cannon placed in the street

nearby, and the German soldier slept for two nights in her house: the war for

him has ended, he told her. When the Russians came to inspect the house, they

found him sitting at the table. He raised his hands in surrender, the Russian motioned him to

the yard where he aimed his weapon at him. Aunt Mariška tearfully and noisily pleaded with the

Russian “Not here, for gossake, not here, please!”. The Russian indicated to

the German to go around the corner of the house - and shot him there. Since

then, Mariška lost a marble or two in her head and could speak of hardly

anything else but of witches and witchcraft. Her husband at the time slept in the

hay in the shed behind the same corner. The bullets penetrated the shed and

woke the uncle Feri in the unkindest of ways.

What

my paternal grandparents did not have up until 1940 (and, except for the radio

and electricity even after ‘till they died in 1955 and 1963 respectively):

-

Antibiotics

-

Car

-

Electricity

-

Photographic camera

-

Internet

-

Bathroom and hot water

-

Microwave

-

Motorcycle

-

Wristwatch

-

Typewriter

-

Gas for cooking

-

Fountain pen

-

Computer

-

Washing machine

-

Radio

-

Television

-

Telephone

-

Dishwasher

-

Artificial fertilisers

-

Credit

-

Tap water

-

Vacuum cleaner

And

what they had up to the year 1940, all made/hunted/processed by their own

hands:

-

Meat (pork, poultry, fish, game –

hares, quail, partridge, pheasants, etc.)

-

Vegetables

-

Fruit

-

Preserves

-

Honey

-

Bread (from purchased flour)

-

Biscuits, cakes, etc.

-

Butter, cheese, etc.

-

Wine (grape, redcurrant, strawberry, rosehip,

even made from breadcrumbs)

Apart

from the above, they also had:

-

Accommodation in the railway house

opposite the Bratislava – Dynamitová továrna station building

-

Uniforms for grandfather

-

Free railway travel within A-U Monarchy, after 1918 within Czechoslovakia

-

Health insurance, paid partly by the

railway

-

Free use of railway land (about 2

hectares)

-

Grandfather’s salary plus pension

after retirement

-

Earnings from the sale of domestic

products.

Grave

in Rača in 2007 (Rudolf Pipaš and Mária were parents of my wife; the stone & inscriptions were paid for in 2011 by Charles & Mirei):

Epitaph.

The grave site above has been demolished by my sister in 2015(?), and the stone used as an extension of garden path (the most expensive metre of a garden path in Prague). Those, whose names appear thereon, belong to us, are part of us...

The grave in Humpolec (below) ended up in similar fashion sometime in 2015-16...

Grave in Humpolec (rodina Hatvaniová = Marie & František. The urn contains ashes of Anna Havelková nee Vašáková, wife of Adolf Havelka):

Apart from these graves there are others: Mireille's uncle Štepán's in Karlovy Vary, various relatives in Humpolec (Škrába), Bratislava (Lepiš) and Jilemnice (Nechanický), possibly Mireille's ancestors Cingel's in Banská Bystrica, etc.

Note.

Preliminary text of this article

has been perused in 2005 by auntie Ruženka (1920-2010), the last living

member of our family from the previous generation, who remembered everything

written herein. I was told that she would have written it completely differently,

but that - basically speaking - is not finding anything substantially incorrect

(with the exception of my description of her sister Helen, who, according to Ruženka, is presented in too rosy terms: according to Ruženka, Helen was known as the family pest, irascible, parsimonious, and unhappy with the “low” social status of the family). I asked Ruženka to write something similar, but she declined. During the remaining few years of her life we exchanged many a letter, and I was able to mine her

memory for many fragments of stories which I duly incorporated into this text.

In 2016 the Publishers of the local magazine in Bratislava (Racan) asked for, & have been granted, permission to publish extracts from these - and other - memoirs (Slovakian versions) contained in my blogs.

No comments:

Post a Comment